The ICTR Remembers

20th Anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide

During 100 bloody days from April to July 1994, Rwanda experienced one of the worst mass atrocities in history. Between eight-hundred thousand to one million Tutsi and moderate Hutu were massacred by Hutu extremists - a rate of killing four times greater than at the height of the Nazi Holocaust.

On 8 November 1994, the United Nations Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR or Tribunal) to locate and prosecute those persons most responsible for the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda. Through criminal prosecution and sentencing, the Security Council intended the ICTR to “contribute to the process of national reconciliation and to the restoration and maintenance of peace” in Rwanda and the region.

Twenty years later, as the international community prepares to commemorate the solemn anniversary of the Genocide, the ICTR recalls the milestones reached and lessons learned in its pursuit of justice for the countless victims. It also highlights the substantial work remaining to be done before the ICTR’s mandate is completed.

THE ICTR IN BRIEF

For the first time in history, an international tribunal - the ICTR - delivered verdicts against persons responsible for committing genocide. The ICTR was also the first institution to recognise rape as a means of perpetrating genocide.

Court hearing during the "Butare case"

Accused in the "Military I" case - Bagosora et al.

The United Nations Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR or Tribunal) to "prosecute persons responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of Rwanda and neighbouring States, between 1 January 1994 and 31 December 1994". The Tribunal is located in Arusha, Tanzania, and has offices in Kigali, Rwanda. Its Appeals Chamber is located in The Hague, Netherlands.

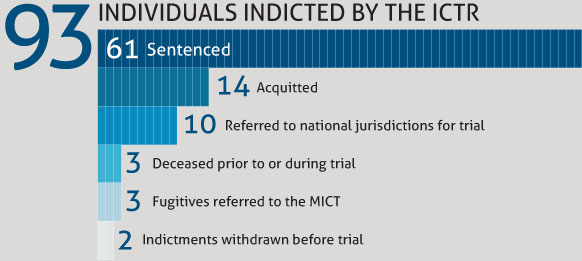

Since it opened in 1995, the Tribunal has indicted 93 individuals whom it considered responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Rwanda in 1994. Those indicted include high-ranking military and government officials, politicians, businessmen, as well as religious, militia, and media leaders.

With its sister international tribunals and courts, the ICTR has played a pioneering role in the establishment of a credible international criminal justice system, producing a substantial body of jurisprudence on genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, as well as forms of individual and superior responsibility.

The ICTR is the first ever international tribunal to deliver verdicts in relation to genocide, and the first to interpret the definition of genocide set forth in the 1948 Geneva Conventions. It also is the first international tribunal to define rape in international criminal law and to recognise rape as a means of perpetrating genocide.

Another landmark was reached in the "Media case", where the ICTR became the first international tribunal to hold members of the media responsible for broadcasts intended to inflame the public to commit acts of genocide.

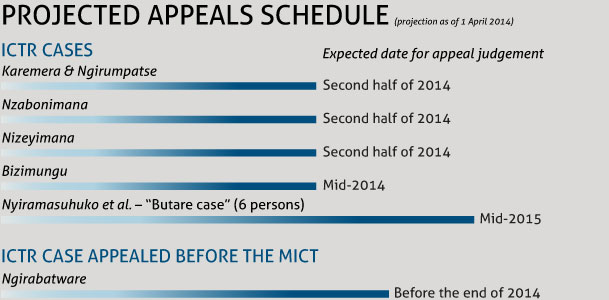

The ICTR delivered its last trial judgement on 20 December 2012 in the Ngirabatware case. Following this milestone, the Tribunal's remaining judicial work now rests solely with the Appeals Chamber. As of April 2014, five cases comprising 17 separate appeals are pending before the ICTR Appeals Chamber. One additional appeal from an ICTR trial judgement is pending before the Appeals Chamber of the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (Mechanism or MICT), which started assuming responsibility for the ICTR's residual functions on 1 July 2012.

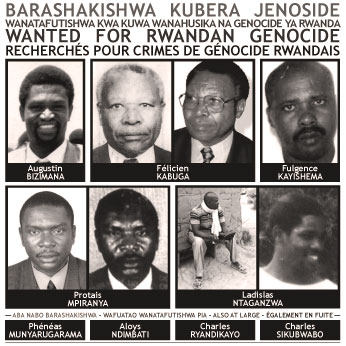

One key residual function assumed by the Mechanism is the tracking and arrest of the three accused who remain fugitives from justice. The ICTR indicted Félicien Kabuga, Protais Mpiranya, and Augustin Bizimana on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity, but the accused have to date evaded justice. The continued cooperation of national governments and the international community as a whole is of paramount importance to the successful apprehension of these fugitives. When apprehended, the Mechanism will conduct their trials and supervise any sentence imposed along with all of the sentences previously imposed by the ICTR.

The ICTR's formal closure is scheduled to coincide with the return of the Appeals Chamber's judgement in its last appeal. Until the return of that judgement in 2015, the ICTR will continue its efforts to end impunity for those responsible for the Genocide through a combination of judicial, outreach, and capacity-building efforts. Through these efforts, the ICTR will fulfil its mandate of bringing justice to the victims of the Genocide and, in the process, hopes to deter others from committing similar atrocities in the future.

MILESTONES

8 November 1994 - The United Nations Establishes the ICTR

In the aftermath of the Genocide and considering reports on "violations of international humanitarian law in Rwanda", the Security Council affirms its determination "to put an end to such crimes and to take effective measures to bring to justice the persons (...) responsible for them".

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda is therefore established with its seat in Arusha, Tanzania.

26 May 1996 -First Detention Facility of the United Nations

The United Nations Detention Facility in Arusha (UNDF), the first UN-built detention facility, is created. To date, the UNDF has admitted more than 80 accused persons, and housed detainee-witnesses from the ICTR, other tribunals, and Rwanda. It has trained UN Security Officers, prison officials from enforcement states, and over 550 Tanzanian prison officers in international detention standards.

9 January 1997 - First Genocide Trial

The trial of Jean-Paul Akayesu begins. On 2 September 1998, the Trial Chamber found Akayesu the former bourgmestre of Taba commune, guilty of genocide. With this case, the ICTR becomes the first international tribunal to enter a judgement for genocide and the first to interpret the definition of genocide set forth in the 1948 Geneva Conventions. In the same judgement, the ICTR also for the first time defined the crime of rape in international criminal law and recognised rape as a means of perpetrating genocide.

July 1997 - Creation of a Unit for Gender Issues and Assistance to Victims of Genocide

This ICTR programme is later bolstered by the launch, on 26 September 2000, of the Support Programme for Witnesses and Potential Witnesses. The continued community engagement of these two programmes reflects the Tribunal's commitment to providing support and care to the victims of the Genocide.

18 July 1997 - Arrest of Seven Suspects in Nairobi

Seven suspects, including the former Prime Minister of the Rwandan Interim Government, are arrested in Nairobi, Kenya as a result of Operation NAKI (Nairobi-Kigali). This operation illustrates the important role national authorities played in bringing those suspected of genocide and other serious violations of human rights to justice. Subsequent tracking operations have resulted in the arrest of 83 suspects. As of April 2014, only three fugitives remain at large to be tried by the Mechanism; six additional fugitive cases have been referred to Rwanda for trial.

1 May 1998 - First Guilty Plea for Genocide

Former Interim Government Prime Minister Jean Kambanda pleads guilty to genocide. This marks the first time that an accused person admits responsibility for genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, and crimes against humanity. By accepting his plea, on 4 September 1998, the ICTR becomes the first international tribunal since Nuremberg to issue a judgement against a former head of state.

12 February 1999 -Mali Becomes the First Country to Sign an Agreement on Enforcement of ICTR Sentences

Subsequent agreements are signed with Benin, France, Italy, Mali, Rwanda, Senegal, Swaziland, and Sweden. These agreements illustrate the important role national authorities play in ensuring that those convicted of serious violations of international law serve their sentences in compliance with international detention standards.

25 September 2000 - ICTR Opens Information Centre in Kigali

Umusanzu mu Bwiyunge, the ICTR Information and Documentation Centre, is inaugurated in Kigali. The Centre's name means "Contribution to Reconciliation" in Kinyarwanda. It hosts a public information area, a library, and the Victims' Assistance Programme. Umusanzu is the centre of many outreach efforts the ICTR conducts in Rwanda and throughout the region.

23 October 2000 - Beginning of "The Media Case"

The trial of Jean Bosco Barayagwiza, Ferdinand Nahimana, and Hassan Ngeze results in the first verdict by an international tribunal holding members of the media responsible for broadcasts intended to inflame the public to commit acts of genocide. In the same case, the Appeals Chamber confirms that the legal doctrine of superior responsibility applies to civilians in leadership positions.

28 August 2003 - ICTR Completion Strategy

The UN Security Council adopts Resolution 1503, requiring the ICTR to develop a strategy to complete its work. The ICTR is currently projecting completion of all but one pending appeal by 31 December 2014. For the final appeal, in the case of Nyiramasuhuko et al. ("Butare"), judgement is anticipated in 2015.

16 June 2006 - Genocide Beyond Dispute

The ICTR Appeals Chamber for the first time takes judicial notice that a genocide against the Tutsi ethnic group took place in Rwanda in 1994. In so doing, the occurrence of the Genocide is recognised as an established fact that is beyond dispute.

24 June 2011 - First Woman Convicted for Rape as a Crime Against Humanity

Pauline Nyiramasuhuko is the first woman to be indicted and arrested by an international criminal tribunal. Following trial, she becomes the first woman to be convicted of genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, and rape as a crime against humanity.

Note: as of April 2014, this case is under appeal.

23 May 2011 - Evidence Preservation Hearings Commence

ICTR commences special deposition proceedings in the case of Félicien Kabuga (pictured) to preserve evidence for use at trial once he is arrested. Similar proceedings were later held in the cases of two other fugitives: Augustin Bizimana and Protais Mpiranya. By holding these proceedings, the ICTR is ensuring that the passage of time does not jeopardize the international community's ability to bring these suspects to trial when they are finally apprehended.

18 December 2011 - First Case Referral to Rwanda

The ICTR Appeals Chamber upholds the first referral of an international criminal indictment to Rwanda for trial, in the case against Jean-Bosco Uwinkindi. A total of eight ICTR cases have now been referred to Rwanda. Two additional cases have been referred to France for trial. Monitoring in all referred cases is presently being conducted by the Mechanism.

2 February 2012 - MRND Politicians Held Responsible for Crimes by their Youth Wing

Highest ranking members of the MRND (Mouvement républicain national pour la démocratie et le développement) political party in Rwanda are held criminally responsible for acts of rape and sexual violence committed by the Interahamwe, their party's youth wing, in the trial of Edouard Karemera and Matthieu Ngirumpatse.

Note: As of April 2014, this case is on appeal.

1 July 2012 - The Mechanism Starts Operations

The Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals formally opens its Arusha branch, one year before its second branch opens in The Hague, Netherlands on 1 July 2013. Pursuant to Resolution 1966 (2010), the Mechanism is mandated with continuing the work of the ICTR and its sister institution the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

20 December 2012 - ICTR Delivers Final Trial Judgement

The judgement in the trial of Augustin Ngirabatware is the last one to be delivered by an ICTR Trial Chamber. The defence appeal from this judgement is pending before the Mechanism Appeals Chamber.

9 September 2013 - Office of the Prosecutor Receives Special Achievement Award

The International Association of Prosecutors confers a Special Achievement Award on the ICTR Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) in recognition of its contributions to the "fight against impunity for the most serious crimes and for taking the initiative to establish a manual of best practices" as a useful guide for national and international prosecutors. In August the same year, the OTP also issues a Lessons Learnt Manual on the Tracking and Arrest of Fugitives, and in January 2014 it releases its "Best Practices Manual on the Prosecution of Sexual Violence Crimes in Post-Conflict Regions".

REMAINING WORK

20 years after the world stood by and witnessed one of the greatest humanitarian tragedies of modern times, the ICTR remains focused on completing its mandate to bring justice to the countless victims of the Genocide.

The ICTR has made significant progress towards the completion of its mandate in accordance with the Security Council's Resolutions. The last trial judgement was delivered on 20 December 2012 in the Ngirabatware case. The focus has now shifted to completing all pending appeals from judgements and documenting the valuable lessons learned in the Tribunal's fight to end impunity.

Starting 1 July 2012, the Tribunal began transferring a number of functions to its successor, the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (Mechanism or MICT). The Mechanism will ensure that critical tasks, such as the tracking and prosecution of fugitives, and protection and support of victims and witnesses who testified before the Tribunal will continue without interruption.

Ongoing Judicial Activities

As of April 2014, the Tribunal's ongoing judicial work consists of five cases, comprising 17 prosecution and defence appeals from trial judgements involving 11 persons. One additional appeal from an ICTR trial judgement involving one person is pending before the Mechanism.

Transition of Functions to the MICT

On 22 December 2010, the United Nations Security Council established the Mechanism to carry out crucial tasks that will outlive the mandate of both the ICTR and its sister tribunal, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The Mechanism's Arusha branch started operating on 1 July 2012.

A top priority for the Mechanism is the tracking and prosecution of the three remaining fugitives wanted for genocide and crimes against humanity. It also is conducting the appeal in the Ngirabatware case, and will conduct any trials, retrials, contempt proceedings, false testimony proceedings, or proceedings for review of final judgements that may arise from ICTR or MICT cases in the future.

Other important tasks of the Mechanism include ensuring the protection and care of witnesses who testified before the Tribunal; the supervision of the enforcement of ICTR sentences; and assistance to national jurisdictions investigating or prosecuting matters related to the Genocide. Of critical importance is the key function of managing the ICTR archives to ensure that the ICTR's extensive judicial and administrative records are preserved and made accessible to the public.

Ongoing Legacy and Outreach Work

This website is the first of many projects the ICTR is undertaking in 2014 to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Genocide, as well as the upcoming 20th anniversary of the ICTR's establishment on 8 November 2014. For the past two decades, the ICTR has been at the forefront of a unique experiment in international criminal justice and has forged partnerships with national authorities in Rwanda, the Great Lakes Region of Africa, and beyond to promote the principles of international justice and accountability.

As stated in the ICTR's Completion Strategy report of November 2013, "[t]he lessons learned in terms of international cooperation between the Tribunal and Member States (...) form a central part of the legacy of the Tribunal as mutual assistance and international cooperation will continue to play a critical role in the management of all international courts and national courts trying crimes of an international nature".

Outreach and Capacity Building

The Tribunal continues to implement major outreach and capacity building programmes as it nears the completion of its mandate. Key tasks include information dissemination, improved communication, and access to the jurisprudence of the Tribunal and other legal materials. These outreach efforts are primarily done through the Information and Documentation Centre (Umusanzu) and the 10 additional provincial information centres located throughout Rwanda. Approximately 65,000 persons have utilized these centres to gain access to the Tribunal's extensive collection of Genocide-related records, briefing materials, training resources, library services, video screenings, and the Internet.

The ICTR also continues to disseminate information to national, regional, and international stakeholders by organising awareness-raising exhibitions and workshops, as well as a major youth sensitisation project.

The Tribunal's Outreach Team continues to engage in a countrywide implementation of the genocide awareness-raising workshops in Rwanda, with approximately 16,000 teachers, students and ex-combatants participating.

Capacity building in Rwanda also continues with the ICTR launching Video Tele-Conferencing facilities in Rwanda in 2012. Additional technology and training is consistently being made available to the Rwandan government and people as the ICTR moves towards closure.

EVENTS AND PROJECTS

ICTR 20th Anniversary Events November 2014

- 20th Anniversary of the Creation of the ICTR - Commemoration Event 8 November 2014

- International Symposium on the Legacy of the ICTR - 6 to 7 November 2014

Draft Programme | Call for Papers - 7th Colloquium of International Prosecutors - 4 to 5 November 2014

Draft Programme

10 April 2014 - ICTR Commemoration Ceremony Statements

- Ban Ki-moon, Secretary-General of the United Nations

- Judge Vagn Joensen, President of the ICTR

- Hassan B. Jallow, Prosecutor of the ICTR and the MICT

- Bongani Majola, Registrar of the ICTR

- Samuel Akorimo, Head of the Registry Arusha branch, MICT

- ICTR Staff Association

Legacy Projects

To ensure that the valuable lessons learned over the Tribunal's 20-year history are not lost, the ICTR is planning a series of legacy-related projects to highlight its contributions to the development of international law, as well as to capture the best practices learned in the prosecution and administration of one of the first international criminal tribunals since Nuremberg.

Please continue to watch this space for updates as to the various programmes currently under development:

- ICTR Legacy Website

- ICTR 20th Anniversary Symposium on International Criminal Law

- International Tribunals' Workshop on Developed Practices and Lessons Learned

- International Prosecutors' 7th Colloquium on International Criminal Law

- Documentary Film

- Best Practices Manual on Referral of International Cases to National Jurisdictions

- Genocide Story Project

If you are interested in getting involved or in supporting one of these projects, please contact the ICTR Legacy Team at ictrlegacy@un.org